Jung's Theory of Psychic Dynamics

Consciousness and the Unconscious

Jung's theory of the psyche is (like Freud's) based on the notion that our conscious experience represents a relatively small part of our total psychological functioning. In reality, much of our experience, and many determinants of our behaviour, exist outside our awareness, in areas of the psyche that are unconscious.

In Jung's analytical psychology, the unconscious tends to compensate for our conscious inclinations. For example, if consciously we constantly seek out stimulation and excitement, the unconscious will attempt to counterbalance this by coercing us to find peace and quiet - perhaps by becoming ill and having to miss a party. Or, if we feel inadequate in our job or social relations, the unconscious may compensate for this through dreams in which we feel competent and powerful.

This compensatory relationship between conscious and unconscious tendencies serves the larger purpose of achieving harmony and balance within the psyche as a whole. Jung attributes this drive towards balance and wholeness to the psyche's inherent 'transcendent function'.

Repression, Complexes and the Personal Unconscious

Each individual develops patterns of unconscious tendencies that derive from repressed emotionally-charged (often painful) experiences, especially those that occur in childhood. Jung calls these unconscious patterns 'complexes'.

For example, we might acquire an 'inferiority complex', based on early experiences of failure, or of being constantly put down by other people. Or, we might develop a 'food complex' based on experiences of associating food with comfort, or with feeling overweight and unattractive.

These unconscious complexes affect our behaviour in significant ways. For example, we might unconsciously expect to fail in important tasks, or we may develop food fads, or even an eating disorder.

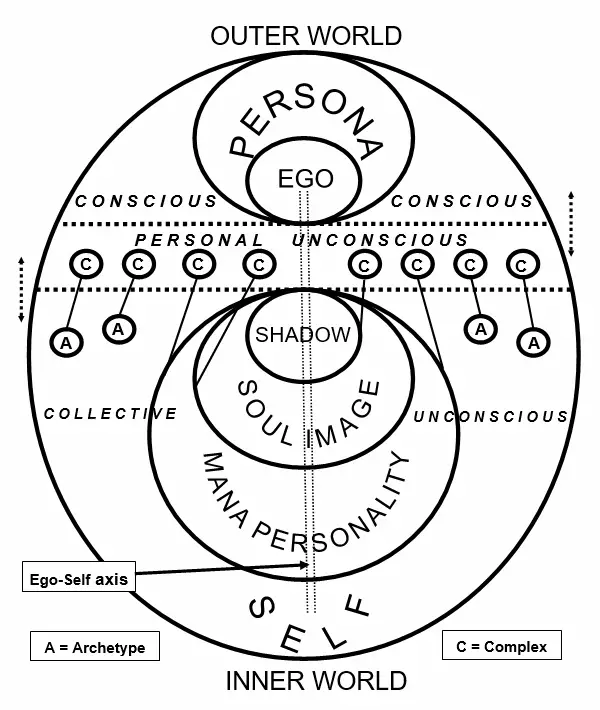

Jung suggests that complexes reside in a region of the psyche that he calls the 'personal unconscious' (because it reflects our personal history of repressed experiences). The personal unconscious is essentially equivalent to the Freudian unconscious.

The Collective Unconscious and Archetypes

Although complexes and the personal unconscious are essentially individual and idiosyncratic, Jung observed many common features in the unconscious expressions of his patients (revealed, for example, in striking similarities among their dream motifs).

These commonalities (as well as explorations of his own inner psychological world) led Jung to the conclusion that each person has access to a shared, species-wide, region of unconscious experience which he calls the 'collective unconscious'.

In the same way that the personal unconscious is populated by individual complexes, the collective unconscious is characterised by a collection of inherited structures that predispose human beings to think, feel and act in similar ways. Jung calls these collective patterns 'archetypes'.

Archetypes may be compared to biological instincts (indeed, instincts are one manifestation of archetypes) but Jung sees archetypes as having much wider significance - influencing not only our behaviour, but also our dreams, myths, fantasies, attitudes and personal narratives.

We may expect there to be as many archetypes as there are universal features of human experience. Thus there are archetypes relating to the human life cycle; to gender and sexuality; to health and illness; to human emotions; to cooperation and competition; to authority; to the natural world; to music, dance and the arts; and to the supernatural and spirituality.

Archetypes cannot be directly experienced. Rather their energies are filtered through social and cultural lenses. For example, Jung believed in the existence of an unknowable archetypal spiritual reality (the God archetype). However, our experience of this spiritual reallity (the God image) is largely determined by linguistic, cultural and artistic conventions. Because different cultures develop different representations of this archetypal spiritual ultimate (e.g., as Jehovah, Allah, Buddha nature, Tao, etc.), so will Jews, Muslims, Buddhists and Taoists tend to experience different versions of the God image.

Archetypes also manifest by channeling their energies through our personal complexes. For example, our attitude towards religion and spirituality will also be influenced by our own personal encounters with religious persons and institutions, especially if these encounters have been emotionally charged. Similarly, our attitude towards maternal figures will reflect not only the Mother archetype, but also social norms relating to mothering and motherhood, as well as our own personal experiences of being 'mothered' (literally or figuratively).

The Stages of Life

For Jung, the most significant archetypes are those that relate to the human life cycle and the processes of psychological development.

Jung understands the essential (archetypal) purpose of human existence to be the achievement of psychological completion, or self-realization, through the balancing and coordination of the various elements of personality.

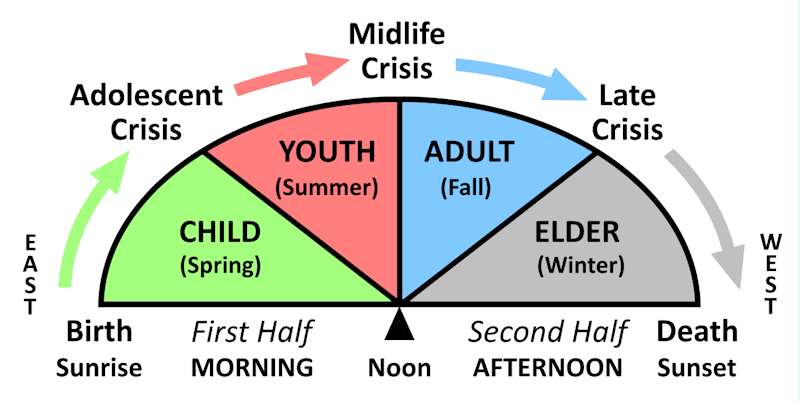

At its simplest, Jung believes that there are two basic (archetypal) stages that, generally speaking, divide our lives into two halves.

Our task in the first half of life (typically from birth to early adulthood) is one of outer development, (the initiation into outward reality) in which our conscious capacities evolve through learning how to adapt to the external world of objects and other people.

In the second half of life, perhaps following a mid-life crisis, we undergo a process of inner development, or the initiation into inner reality, involving the exploration of, and adaption to, the inner world of the unconscious.

How easily a person adapts to the demands of outer and inner development depends to some extent upon his or her psychological type.

Because extraversion is naturally orientated towards the outer world, extraverts often find that the first half of life runs relatively smoothly (especially in terms of developing social relationships).

Introverts, on the other hand, because they are more naturally attuned to the inner world, often find social adjustment in the first half of life quite a challenge. Introverts may, however, be able to compensate effectively for this by focussing their energies on more solitary, introverted pursuits (e.g., reading, school work, hobbies).

In the second half of life, the tables are turned. Extraverts may now find difficulty in approaching the unconscious and meeting to the demands of inner development, whereas introverts tend to be more open to these tasks.

Each half of life can itself be divided into two stages which are also typically separated by a psychological crisis. Thus we can identify four major stages of life (comparable to the four seasons) and three main life crises.

The adolescent crisis is marked by the struggle for independence from parents and adjustment to new sexual feelings and relationships. The mid-life crisis is generally associated with assessing and questioning the success of one's outer life (career, family relations, etc.) and a turning inwards to recognise the call of strange unconscious impulses. The late crisis occurs when we are forced to confront our own mortality. This may be triggered by serious illness or increasing frailty, or by the frequent deaths of peers, or by a near-death experience.

The Jungian Life Cycle

Outer Development

In the first half of life, two fundamental psychological structures emerge from the originally undifferentiated ground of the unconscious Self. These structures are (1) the ego, and (2) the persona. When successfully formed and coordinated, the ego and persona enable us to function adequately in our relations with the outer world.

Ego

The ego is essentially our centre of consciousness and agency, or our conscious sense of self. It is what we ordinarily experience as being 'me'.

According to Jung, the ego emerges as a conscious satellite of the unconscious Self and generally remains connected to this larger Self via the psychologically stabilising ego-self axis (similar to the way that the Moon remains in stable connection to the Earth via gravitational attraction).

However, in very fragile personalities, or in cases of serious psychological breakdown, the stabilising ego-self axis may become compromised, leading to major problems in adjusting to the outer world.

Persona

The persona is the set of acquired attitudes and behaviours that enable us to function adequately and satisfactorily in our relations with the outer (especially social) world. It comprises all the roles and performances that we have learned to adopt in our social interactions.

Essentially, therefore, the persona is a theatrical mask (Latin: persona) that we wear in order to please other people, or impress them, or to gain social rewards.

In practice, we learn to develop many different masks (personae) depending on whom we are with. Thus we may have one persona for our parents, another for our friends, and yet another that we express at work.

For most people, learned personae are generally consistent with social norms and cultural expectations, especially those relating to their gender, sexuality, age and other physical attributes.

Individuation and Inner Development

The majority of Jung's writings focus on the process of inner development, leading to the ultimate goal of psychological integration, or individuation, and the conscious realization of the archetype of the Self.

Jung sees this process as involving a series of phases in which the focus is on recognising and integrating four archetypal aspects of our inner being. These are: (1) the shadow; (2) the soul image (anima or animus); (3) the mana-personality, or archetype of power; and (4), the realized Self.

Shadow

The archetype of the shadow represents aspects of our being that are denied, repressed or submerged because they are felt to be unacceptable.

Generally these are unhygenic, immoral, or antisocial characteristics (negative shadow) but there can also be a positive shadow (comprising, for example, spontaneity, humour, or warmth) which has been repressed because these qualities have been repeatedly frustrated or criticised.

Very commonly we project our shadow onto other people, seeing them as exhibiting the very characteristics that we find difficult to acknowledge in ourselves. This shadow projection is generally directed at individuals or out-groups that we fear, or that we consider strange or inferior to ourselves.

As well as projecting our own personal shadow, social groups (e.g., gangs, political parties, tribes, and nations) can also project their collective shadow onto opposing or foreign groups.

For Jung, the confrontation with our personal shadow is the first step in the difficult journey of inner development. This requires a willingness to acknowledge and take responsibility for our own unacceptable characteristics, rather than continuing with denial and projection.

Soul Image

The second phase in the journey towards self-realization involves the encounter with an inner 'other' personality that personifies the creative potential of the unconscious.

This 'soul image' is often experienced in dreams and fantasies as a fascinating (though sometimes intimidating) opposite-sex figure. Because of this contrasexual aspect, the soul image generally manifests differently in men and women. For males, the soul image is usually experienced as having 'feminine' qualities (the anima) whereas, for females, it tends to represent 'masculine' attributes (the animus).

Our task during this phase is to recognize and accept the contrasexual qualities of the anima or animus as aspects of our own being that provide creative energy and the promise of psychological counterbalance and completion.

Thus the male must be willing to accept his own creative inner femininity rather than simply seeking out feminine qualities in women. Similarly, females must accept their creative inner masculinity instead of searching for these complementary characteristics in men.

Essentially we must realize that the creative impulse and our yearning for psychological completion comes from within our own psyche and therefore can never be fully satisfied by another.

Mana Personality

As we explore more deeply into the inner world, we may experience a profound sense of spiritual power or guidance. Jung views these experiences as manifestations of the mana personality (mana is a Polynesian word meaning supernatural power).

Unlike the soul image, the mana personality is generally personified (e.g., in dreams and visions) as a same-sex figure. For men, it may be experienced as a Wise Old Man, Sage, or Sky Father, whereas, for women, it may appear as a Wise Woman, Sibyl, or Earth Mother.

Although the mana personality represents our fundamental male or female power, it is vital that we do not identify our own personality with this archetype, because this can lead to megalomania or to the development of a guru complex. Rather, we should acknowledge and accept the mana personality as one important aspect of the psyche, whose energies should be coordinated and integrated with those of the other developmental archetypes.

The Realized Self

As previously noted, the Self (whole psyche) is originally unconscious and undifferentiated. Psychological development (outer and inner) involves an expansion of consciousness through the stepwise emergence and coordination of the differentiated psychic structures discussed above.

For Jung, the ultimate goal of psychological development is the conscious realization of the archetype of the Self, representing balance, harmony and integration among all elements of the psyche.

However, it is important to recognise that the realized Self is a theoretical goal that can never be fully achieved. This is because we can never become conscious of everything within the psyche - the unconscious will always remain.

While full self-realization is impossible to achieve, it continues to call us - in our dreams and imaginations, and through symbols, myths and philosophies that represent ideals of wholeness, harmony and completion. Indeed, Jung believed that engaging meaningfully with such symbols and narratives (e.g., painting mandalas, studying spiritual works) could assist in our own progress towards realization of the Self.

Jung's Model of the Psyche and

Psychological Development

Further Reading

Daniels, M. (2015). Self-Discovery the Jungian Way: The Watchword Technique (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Daniels, M. (2023). The Watchword Personality Test: A Complete Practical Guide. watchwordtest.com.

Jacobi, J. (1968). The Psychology of C.G. Jung, 7th edn, Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Jung, C.G. (ed.). (1964). Man and His Symbols. Dell.

Jung, C.G. (1966). Two Essays on Analytical Psychology, 2nd edn. Routledge & Kegan Paul. (Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Vol. 7).

Jung, C.G. (1968a). The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, 2nd edn. Routledge & Kegan Paul. (Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Vol. 9, Part I).

Jung, C.G. (1968b). Aion: Researches in the Phenomenology of the Self, 2nd edn. Routledge & Kegan Paul. (Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Vol. 9, Part II).

Jung, C.G. (1969). The Structure and Dynamics of the Psyche, 2nd edn. Routledge & Kegan Paul. (Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Vol. 8).